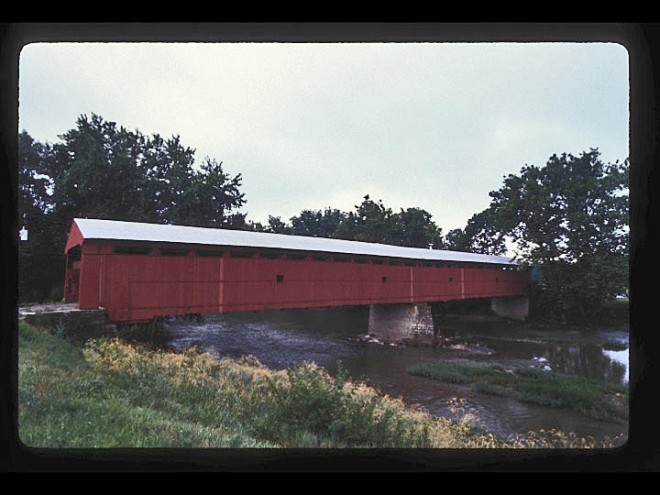

The Eldean Covered Bridge in Troy, Ohio, one of only about a dozen surviving long truss covered bridges.

Last month, the National Park Service announced the designation of 24 new National Historic Landmarks. The new Landmarks represented a wide diversity of historic and sociological significance, and included the Medgar and Myrlie Evers House in Jackson, Mississippi; the Our Lady of Guadalupe Mission Chapel (McDonnell Hall) in San Jose, California; the Pauli Murray Family Home in Durham, North Carolina; the Eldean Bridge in Miami County, Ohio; the West Union Bridge in Parke County, Indiana; and the May 4, 1970, Kent State Shootings Site. I encourage my readers to follow the above link to learn about each each of these as the significance to local or national history for each one is clear; however, today I’d like to focus on another such recently-designated Landmark: the Greenhills Historic District.

Greenhills, Greenbelt, and the Resettlement Administration

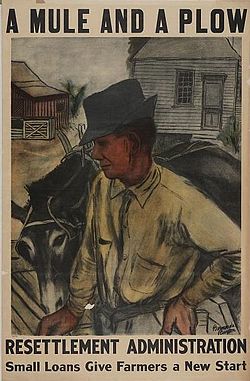

The federal government’s Resettlement Administration (RA) constructed the original buildings in Greenhills as one of three, or perhaps four greenbelt cities; the others are Greenbelt, Maryland, Greendale, Wisconsin, and sometimes included is Roosevelt, New Jersey, which the RA approved, but had little to do with its eventual completion. Never popular, or properly funded by Congress, the RA lasted only from 1935 -37.

The mission of the Rettlement Administration was to create decent living quarters for those who suffered most during the Great Depression. This included migratory workers, farmers displaced by the catastrophic drought known as the Dust Bowl, and certain urban populations, such as Jewish garment workers. The greenbelt towns were conceived as self-sufficient cooperative communities, admired by professional planners and reviled by political opponents as socialist. They got the name “greenbelt”, because the plan laid out for them included a surrounding green belt of undeveloped land. Ironically, this is perhaps the beginning of the uneasy relationship between agriculture and suburbia.

Early Twentieth Century Suburbia, Early Twentieth Century Agriculture

The end of the nineteenth century saw many cities suffering from image problems, perhaps more so than today. Newly-arrived foreigners and poor sanitation were facts of life that led to a perception of cities as centers of crime and disease, and densely-packed man-made edifices as an “unnatural” environment for humanity. The early part of the twentieth century saw observable numbers of people choosing to live in surrounding communities. However, urban areas were still concentrated enough to provide important markets for agricultural products, and farm produce prices rose 87% from 1900-1910. Farmers continued to do well until 1918, when the end of WWI and an influenza pandemic slowed economic growth, signaling the end of the Golden Age of Agriculture. Still, farmers with access to large urban markets, like my grandparents, found ways to make a living, even with the onslaught of the Great Depression.

New Deal progams, like those administered by the Resettlement Agency, gave way to post-WWII veterans’ programs that encouraged suburban home-buying. The automobile allowed these suburban developments to “leap-frog” into farmland. It wasn’t necessary for them to be close to one another, any old jalopy could get you where you wanted to go. Unfortunately, development began to destroy the very nature that suburbanites craved.

Enter Levittown, Long Island, the Mecca of mid-century development, and listen to these voices:

“There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings…The town lay in the midst of a checkerboard of prosperous farms, with fields of grain and hillsides of orchards where, in spring, white clouds of bloom drifted above the green fields…” –– Rachel Carson, “Silent Spring”, 1962.

This was the ideal, the desire of the heart. A description of the reality follows.

“… suburbanization itself involved environmental destruction. Consider just what it took to build the 17,000 (homes) that made up a huge development like Levittown, NY… Levittown’s builders razed much of what was left of the only naturally occurring prairie east of the Alleghenies, the Hempstead Plains. Houses and lawns replaced natural topsoil, plant life, and vegetation … Moreover, to provide wood for the houses, the Levitts bought a timber company in Northern California. Levittown’s construction thereby had a significant hand in the stepped up destruction of old-growth redwood forests on the far side of the Continent.” — Christopher Sellers, “Nature Transformed: the Environment in American History”, 2010.

The historical perspective here seems to be telling us that farmers need a certain amount of population to create demand for what they supply. Really simple economics, right? And people are going to live where and how they want today’s American society, and many will tell us that’s a good thing. Perhaps there is an uneasy relationship between agriculture and suburbia, but it still can be a mutually beneficial one.

Let’s do some history from my own point of view: when we moved to Cincinnati in 2001, my wife and I could find no plausible explanation for the lack of availability of fresh, local food. Farms were abundant; farm stands were absent. Farmers grew field corn and soybeans and sold them to big processors like Archer Daniels Midland or Cargill. None seemed interested in sweet corn and green beans sold to consumers. But times were good, and the Cincinnati suburbs were expanding rapidly.

Farms that grow cash crops like field corn and soybeans need to be fairly large to be profitable. By contrast, farms surrounded by suburban development tend to be smaller. Two factors are at play here: large established farms may be too expensive to maintain in a more urban environment, and these are often sold to be developed, in whole or in part. Established family farms over time get smaller as they are divvied up to younger generations. These smaller farms can be very successful at direct marketing, in part due to their proximity to the local population.

Editor’s note: All images are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Cincinnati’s growth has slowed since the beginning of this century, but it was named the #6 on WalletHub’s 2016’s Best and Worst Foodie Cities, indicating just how far that 2001 trend has turned around. The website used several interesting parameters to determine their ratings. Some were obvious, like the cost of groceries, beer, and wine, the availability of healthy options, farmers markets, and CSAs. Then they become more creative, such as the ratio of full-service to fast-food restaurants. Lastly, some categories in which Cincinnati excelled by ranking in the top 5: craft breweries and wineries, specialty food stores, and most ice cream shops, per capita. (In fact, Flannelnerd pities the fool who thinks he can open an ice cream parlor in this town!) Without suburban growth, Cincinnati would be ranked in the bottom 50 of the 150 cities, along with Toledo, Akron, and Fort Wayne, not in the top 10. Take advantage of all it has to offer.